The turbulent Italian context in 1944

"[…] the State that will emerge from the immense trouble will be yours and as such you will defend it against anyone dreaming impossible comebacks. Our will, our courage and your faith will give Italy her face back, her future, her life possibilities and her place in the world. More than hope, this ought to be, for you all, a supreme certainty."

"Long live Italy! Long live the Republican Fascist Party!” The words of Benito Mussolini on Radio Monaco still resound in the loudspeakers in the squares of cities and villages in northern Italy, what is now called Repubblica Sociale Italiana (‘RSI’, in short). A state in the state, opposed to the Kingdom in the South, kept up by the fugitive king, Vittorio Emanuele III, and high commander, General Badoglio, taking refuge in Apulia. A government born of a coup, a discharge, an arrest. And a liberation. The Allies -Americans, Brits, Canadians- landed in Sicily July 10, 1943 and the armistice between Italy and the Angloamericans was signed in Cassibile, Sicily on September 8. Mussolini had been freed of his captivity on the Gran Sasso massif thanks to a daring raid conducted by german paratrooper forces, who flew to the target aboard glider planes, silent as eagles. Not a shot had been fired and the Repubblica Sociale had been founded, out of the will of the Duce and the Führer. The need for territory to deny the Allies the room to maneuver their forces on the peninsula was part of the german ‘retention plan’. They expected the Italians to betray. Thus began Operation Achse and with it the Nazi-fascist occupation of centre-north Italy.

The words of Benito Mussolini on Radio Monaco still resound in the loudspeakers in the squares of cities and villages in northern Italy, what is now called Repubblica Sociale Italiana (‘RSI’, in short). A state in the state, opposed to the Kingdom in the South, kept up by the fugitive king, Vittorio Emanuele III, and high commander, General Badoglio, taking refuge in Apulia. A government born of a coup, a discharge, an arrest. And a liberation. The Allies -Americans, Brits, Canadians- landed in Sicily July 10, 1943 and the armistice between Italy and the Angloamericans was signed in Cassibile, Sicily on September 8. Mussolini had been freed of his captivity on the Gran Sasso massif thanks to a daring raid conducted by german paratrooper forces, who flew to the target aboard glider planes, silent as eagles. Not a shot had been fired and the Repubblica Sociale had been founded, out of the will of the Duce and the Führer. The need for territory to deny the Allies the room to maneuver their forces on the peninsula was part of the german ‘retention plan’. They expected the Italians to betray. Thus began Operation Achse and with it the Nazi-fascist occupation of centre-north Italy.

After the armistice, for a time, there was hope, breathing the scent of a freedom still afar. The population, however, felt guideless, lost with no one at the helm. Still the new wind, that feeling of lack of real rules, after a moment of confusion, freed the conscience of the citizens from the bounds that the regime at first, and the King or the Duce of RSI later, tried to impose on the populace.

Freedom with curfew. Censorship. Police cordons through the cities. Soldiers of the King firing on protesters. Germans in your home. Fascist hierarchs hidden and protected by the Royal Army. The illusion of peace melted away like snow in the sun.

The war was going on.

Yet the rule of force as the sole mean to regulate life, the quashing of rights and the exploitation of the populace had lit a flame that dwelt, hidden, under the embers of an iron will. It gave life to a struggle growing from the bottom, out of those who felt the urge to take part in what would become the liberation of Italy. The armistice with the Allies was just a way for the establishment to remain in power and the people, weary and disoriented, were tired of being witness -and unwilling actor- of their own tragedy. So arose the first partisan groups - by self generation, not by legacy – (G. Bocca).

It ceased being a war of army versus army, nation versus nation, soldier versus soldier. Now it was a war between Italians following an ideal and Italians following another ideal.

A civil war running in the background of the occupation. Hard, violent, merciless, the Nazi-fascists were desperately holding their ground against increasing pressure from the Anglo-American army marching north under the command of general Alexander. The minute spreading of Wehrmacht units in hundreds of italian towns and villages brought about the nazi ‘final solution’ over Italy as well, with massive round-ups and deportations. Jews, political opponents, bandits, rebels, soldiers still loyal to the King… no one was spared.

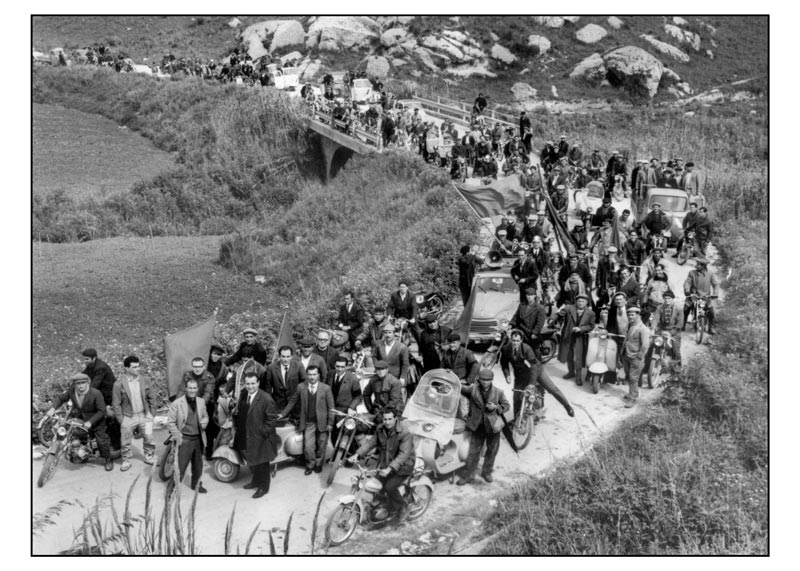

While the Allied forces gained ground, partisan formations steadily grew in numbers, recruiting common people young and old, men and women alike. Most formations referred to the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (CLN, in short) as an umbrella authority, and independents, not recognized by the CLN, were often treated like rogues by other anti-fascists, sometimes even executed. As the formations increased their number and efficiency, strikes against fascist and nazi targets intensified. It wasn’t traditional warfare –partisans were still no match for regular units- it was guerrilla, fought on the mountains, in the forests, along the valleys. The bolder the feats of the “bandits” became, the harsher the nazi would retaliate against civilians. Be it out of desperation at seeing the Allied armies pressing on, frustration for being unable to strike back at the rebels, or simply longing for revenge against a population that hated them, the nazi troops acted with thorough brutality.

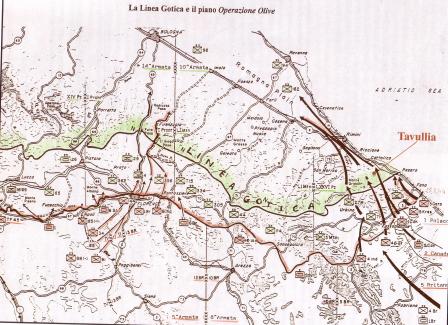

The Gothic line and the Tuscan-Aemilian Apennines

After September 8, 1943 armistice, the strategy of Field-Marshall Albert Kesselring, German Commander-in-Chief South, was that of a fighting retreat. Faced with superior numbers, he planned to fall back on a fortified line after another, preserving his forces as much as possible while inflicting the highest damage on the enemy, hopefully grinding the Allied onslaught to a halt before reaching northern Italy and thus denying them access to the heart of Europe. The best of said defense lines lay across the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines from Massa on the Tyrrhenian coast to Pesaro on the Adriatic, passing through the Arno river valley and the provinces of Modena and Bologna. Imposing forced labour on thousands of italian civilians in the so called Organisation Todt, they heavily fortified their positions along the line, building countless trenches, bunkers, gun pits and machine-gun nests and finally named it Gotenstellung, or ‘the Gothic line’. The Allies reached it in the summer of 1944 and quickly laid down Operation Olive to try and overcome the german defenses before the autumn rains made it all but impossible, delaying their advance until the next spring. For this feat to be accomplished, one of the critical break-through points was the area or Monte Sole, with the Futa and Giogo mountain passes leading into the Padan Plain and to Bologna. The Germans stood a good chance of holding long enough but partisans could be a game changer in that crucial territory, so, on august 12, 1944 Kesselring issued a General Order to quash any resistance fighting, practically according German commanders free rein on how to achieve the goal.

12 August 1944: KESSELRING's General Order (abstract)

1. Begin the most vigorous actions against armed bands of rebels, against saboteurs and criminals that in any way with their injurious activity hamper the conduct of the war and perturbate public order and safety.2. Take a percentage of the population hostage in those places where armed bands are known to operate and shoot said hostages every time an episode of sabotage should happen in one of those places

3. Execute acts of retaliation up to the point of burning the houses that stand in areas where gunfire should be directed against German units or individual soldiers.

4. Publicly hang individuals identified as murderers or bosses of armed bands.

5. Hold the inhabitants responsible in those villages where roads or telegraph lines should be subject of sabotage.

6. The preceding points are to be made known to the citizens, who must effectively cooperate in order to prevent elements in the pay of the enemy from committing the aforementioned crimes.

Where history blurs into fiction: Montelupo and the surrounding valleys

Montelupo is a fictional small village huddled on the slopes of Monte Sole, just north of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennine ridge. In our narrative, it’s “the first village beyond the Raticosa pass”. To the east would lie Monzuno, to the west Grizzana Morandi, to the north Marzabotto and Sasso Marconi and beyond, Bologna.

Of the few villages spread out just beyond the mountain passes separating Tuscany and Aemilia our Montelupo is the first in the line and the most relevant: it is a necessary point of passage for the Allied troops on their way to the Padan Plain. A few stone huts, a communal oven, an inn… even a brothel, offering discounted rates for the military. The war is coming to an end, or at least that’s what the local population thinks. The Germans are clearly about to retreat, in the past weeks they have been dismantling gun positions, comm lines, aerials, even whole sections of railway track. Sooner or later, life is bound to return to normality. The people of Montelupo are at peace, it is hearsay that the Allies are just beyond the mountain pass, and someone even claims to have spotted their vanguards on the heights with a binocular. News of the liberation of Florence is confirmed by now, Bologna will be next and the time can’t be far. The local partisans are coming more and more out of their hideouts, sometimes even breaking their cover allowing themselves to be seen in the village. Stella Rossa, the red star, is the name of the independent partisan brigade founded by Ettore Gamberini –battle name Sirio. They control the woods around Montelupo and fight the guerrilla war against the German oppressor. The village priests do what they can to mediate, or better said, Don Cattani does: it is rumored that Don Montanari joined the partisans instead. The ‘Podestà’, the mayor, Giulio Castaldi, in accord with the chief of the ‘Brigate Nere’ fascist militia, Augusto Malagoli, tries to preserve the balance. Maybe, once the war is over, winners and losers, whoever they may be, will be able to sit together for a glass of wine at the inn and life will return to normality, like before, when war was just a distant fear. Currently, Montelupo is inhabited mostly by women and, like many other women all over Italy, they had to roll up their sleeves to get by -Mussolini’s 1938 laws restraining women labor notwithstanding. Most men are gone: some are serving in the military, some went missing in the woods, some are simply dead. The children have been sent off to safer places down the valley, away from the frontline, staying at friends’ or relatives’. Hopefully their mothers will soon be able to go and fetch them back.

Daily Life

Life in occupied Italy is a daily struggle to survive the perils of war, though the people of Montelupo may be finally close to seeing the end of it. Most men left the village, sooner or later during the war. Some will never come back. A few remained to keep things going but it’s the women who are now at the core of village life. Someone had to take care of the fields, the animals, everything. Gone the able men, sisters, wives and a few of the old parents were left in charge. They try to get by, day after day: they collect what little supplies are available through their ration books, they bake bread, take care of the chickens, mend clothes waiting for the end of these troubled times. After all, who cares for a small village like Montelupo? The young, reckless, or maybe brave, have left their homes to live in the woods, sleeping one night in a shackle, another under the starlit sky and a third… who knows where? Living finally free of all the bounds that were imposed on them in the preceding years, to make their voice heard, to fight against the Fascist regime and the Nazi occupation. The villagers of Montelupo are concerned each with their own, they don’t think as a group. One is saved alone, one way or another. They’re afraid of fires, retaliations, anything that can take away their house and what little they’ve got left. Those who don’t want to take sides must still succumb to the demands of the German invaders, too strong and ruthless to accept a refusal. The only feasible strategy is not to compromise oneself with the partisans, pretending there’s no occupation and the German rule is legitimate.

Sure, in the hamlet of Montelupo, like everywhere in the RSI, one can find Fascist loyalists, close to the Brigate Nere and the Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana, as well as supporters of the rebels, secretly providing them with food, clothes and valuable information. Yet the vast majority just wants to survive at all costs. They dislike the German occupants, but they accede to their requests in order to be spared. At the same time they do something for the rebels too, even if it’s dangerous, in a tricky game of balance. They walk on a thin line trying not to fall out of grace with either side, anxiously waiting for the arrival of the Allied forces to liberate them. After all, the Germans are really going away soon.

Yes, liberation, the end of the war. The Allies are near and hope is timidly beating again in the heart of the inhabitants of Montelupo, just at a time when a feeling of helplessness and exhaustion is slowly overcoming those who spent themselves too much in the strenuous last few years.

Life goes on. For everyone.

General info about the larp

You can find all you need to know on the International Home Page for the larp.